Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Conserve. Protect. Enjoy.

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

By Starr AndersonPosted April 10, 2025

Glencoe Cemetery in Big Stone Gap

Cemeteries are outdoor museums that tell the stories of generations past. But time and the elements often take a toll on these sacred spaces, which is why historic preservation specialists, like Burke Greear, are so important.

Ranger Greear works at Southwest Virginia Museum Historical State Park and has extensive knowledge of historic cemetery and monument preservation. Over the years, he’s conducted thousands of grave headstone and monument conservation treatments, from basic cleaning to complete reconstruction.

Now, Ranger Greear is leading a Historic Cemetery Preservation Workshop to share his skills with the community and bring awareness to proper stone conservation methods.

Read our Q&A below to learn more about Ranger Greear’s experience and what he’ll cover in the workshop.

Q: Can you tell us about your background in historic cemetery and monument preservation?

Ranger Greear

A: Historic cemetery and monument preservation are relatively new areas of conservation work. For example, not long ago (within the last 25 years) the National Park Service, National Cemeteries Administration and other major conservation agencies that manage cemeteries as part of their resources would pressure wash headstones or use abrasive means of cleaning the surfaces of monuments. But minds and methods started changing.

I had just graduated with my bachelor’s degree in museum studies from Tusculum University, so I was ready and eager to take up conservation work in earnest. It was also at this time that I secured a position with the National Park Service. Among my responsibilities was to care for an actively operating National Cemetery that boasted a historic presidential burial site as well as final interment for over 3,000 military veterans.

While with NPS I had the opportunity to attend a National Cemeteries Summit in Niagara Falls, New York. Among the topics being discussed were the changing methods of properly cleaning stone monuments, namely the marble markers used by the military.

After this conference, I began participating in what would be an eight-year-long study by the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, an organizational arm of NPS, concerning the use of quaternary ammonium compounds to remove biological growth and associated staining from stone substrates, especially historic marble.

This was a “do no harm” approach to stone conservation, and that was a relatively big shift from the days of bleach, stiff brushes and pressure washers.

As my position continued to allow me to explore historic stone conservation more deeply, I ultimately received training from the NPS National Preservation Training Center. Through this work, I learned how to properly lift, level, reset and repair damaged monuments using essentially inert products and traditional methods.

Q: How many cemeteries have you worked in over the years?

A: At this point, I have lost count of the number of cemeteries that I have worked in, but it is safe to say several dozen, resulting in approximately 4,000 individual stone conservation treatments, ranging from basic cleaning to full reconstruction. Most of my work has taken place in Eastern Tennessee and Southwest Virginia.

Q: What are some of the misunderstood aspects of grave headstone and monument preservation?

A: It is common to think, when cleaning stone for example, that you can do anything you want to a “rock,” and you won’t damage it. I mean, it’s just a rock, right? Wrong. Stone types can have different “personalities.”

They react differently to different conditions, and it is easy to unknowingly create adverse conditions simply by using harmful products and methods. It’s not exactly rocket science, but there is a right way and unfortunately, lots of wrong ways.

Q: What method of grave headstone and monument preservation do you use and teach to others?

Ranger Greear

A: I always use the least invasive, least abrasive cleaning method possible. Many stains can be removed with just water, a little agitation with a soft-bristled brush and a rinse. If there is biological growth present, i.e., fungus, algae, moss, lichen, etc., a prepared solution called D/2 is applied to inhibit further growth and begin the breakdown of any residual staining.

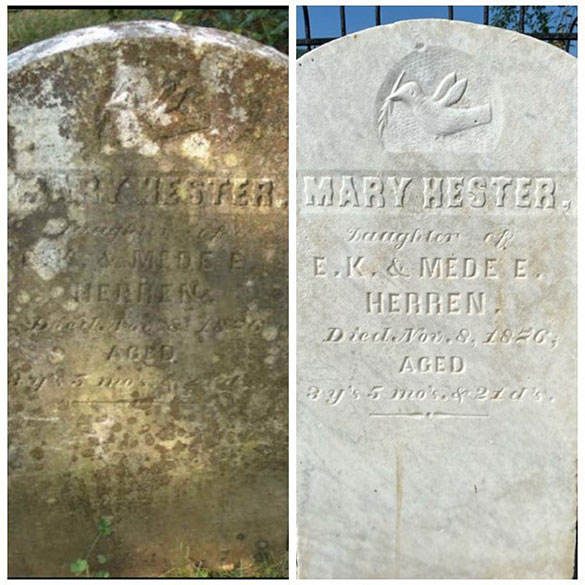

Once the biological growth is under control, which may take several weeks, a final scrub is performed, and the stone is then retreated with the D/2 solution and left to the elements.

Over the next few weeks, the stone will revert to its most natural, unpolluted condition. All of this occurs without abrasive salts, acids or bleach, which can damage the stone long term.

Q: In addition to proper preservation methods, workshop participants will learn how to identify different types of stone and monument styles. Can you describe some of these for us?

A: Nowadays, most grave monuments are very similar in general style and are typically made of granite. Prior to the wide use of granite, marble was the stone of choice. Predating marble, monuments were generally fashioned from whatever the local geologic conditions dictated. In Southwest Virginia, that was typically limestone and some occasional sandstone.

Unlike current gravestones, historic monuments can be as different as the lives they represent. Different styles such as tablets, ledgers, obelisks, pedestals and others were generally covered with symbolism, poems, epitaphs, biographies and other information. Older monuments continue to stand more clearly as individual testaments than do the modern “cookie cutter” headstone styles.

Among the rarest monuments to encounter were made by the Monumental Bronze Company in the late 1800s. Often referred to as white bonze, the monuments were not made from bronze at all, but rather zinc. The company went out of business in the early 1900s because consumers did not trust that the monuments would outlast stone. They were wrong.

Q: You mentioned symbols, which you’ll also cover during the workshop. What are some of the symbols you’ve seen and what do they mean?

A: The most common symbol I found on historic monuments is the human hand (Virginia recognizes pre-1900 burials as historic). Seen as an important symbol of life, hands carved into gravestones represent the deceased's relationships with other human beings and with God. Cemetery hands tend to be shown doing one of four things: blessing, clasping, pointing and praying.

Here are some other symbols and their meanings.

Q: It sounds like participants are going to walk away from this workshop with a new set of skills. Who do you encourage to sign up?

A: Whether you’re a genealogist, historical researcher, cemetery maintenance personnel, working on a family plot or simply fascinated by the stories buried beneath our feet, this workshop is a unique opportunity to learn and become a steward of history.

Everyone will walk away being able to confidently and effectively use “do no harm” methods of historic cemetery and monument preservation.

While participants will know how to properly care for headstones and monuments after the workshop, it’s important to remember to ask for permission before entering a cemetery to clean one.

You should ask for permission directly from family if they still exist because the monument is still technically their property, or at the very least, ask permission from the cemetery itself. Some cemeteries may have a single caretaker or a full managing board. Permission is very important. I won’t work without it.

Q: Why is the Historic Cemetery Preservation Workshop important to you?

A: I believe that the reason for preserving monuments is to make them last as long as possible, like the memory of the lives they represent. The goal is not to make the stones as clean as possible as fast as possible. That’s our own need for instant gratification, and, as the old saying goes, haste makes waste. Showing members of the public how to properly take care of these historic stones and then sending them out with the basic knowledge to do so is very rewarding.

The Historic Cemetery Preservation Workshop will be held on April 12 and Sept. 20 from 1 to 4 p.m. at Big Stone Gap’s Glencoe Cemetery.

The fee for the April workshop is $40 per participant, which includes a professional-grade gravestone cleaning kit to take home. The kit contains a 5-gallon bucket with a lid, a large Tampico utility scrub brush, two smaller brushes for lettering and detail work, six bamboo skewers for getting into tight areas, two pairs of nitrile gloves, a set of three different-sized white plastic scrapers and one 32-ounce spray bottle of D/2 Biological Solution.

The fee for the September workshop is $25 as this session focuses on intermediate conservation skills and does not include a take-home cleaning kit. The goal of the workshop will be to demonstrate and perform intermediate conservation treatments for all of the most common gravestone and monument preservation dilemmas, including dirt/biological growth, resetting tilted/fallen stones and rejoining/repairing fractured stones, all of which are so common throughout many cemeteries in the area.

Registration for both workshops is limited to 15 participants. The registration deadline is the Friday before the workshop.

For more information and to register, please call Ranger Greear at 276-523-1322 or email burke.greear@dcr.virginia.gov.

Categories

State Parks