Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Conserve. Protect. Enjoy.

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

By Emi EndoPosted January 31, 2024

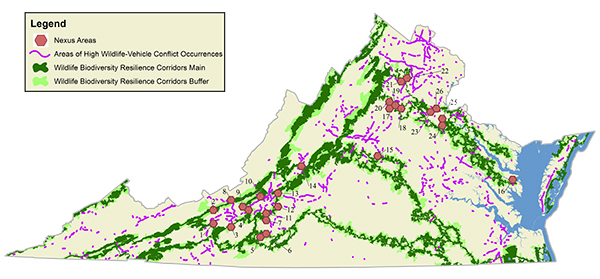

A new map of high-quality, connected habitats in Virginia that support native wildlife shows locations that are being investigated for measures, such as wildlife crossings, to both improve driver safety and help stem biodiversity loss.

The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation created a map of high-quality habitats for native wildlife, called Wildlife Biodiversity Resilience Corridors, which identify important areas of land for wildlife corridor conservation actions and ecosystem health.

Click the map to view a larger version.

Click the map to view a larger version.

As habitat for wildlife becomes increasingly fragmented by roads and other development, and further impacted by environmental factors related to climate change, many species must rely on wildlife corridors for dispersal to suitable habitats, as well as to find food, water, shelter and to reproduce.

In the United States, 40% of animal species are at risk of extinction, according to a February 2023 report from NatureServe. The report also found that 41% of ecosystems are at risk of range-wide collapse.

To fulfill a requirement under state legislation, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources led a multi-agency team to write the state’s first Wildlife Corridor Action Plan.

The plan outlines areas in Virginia with the highest numbers of wildlife-vehicle conflict, especially for bears and deer.

Photo courtesy of Virginia Transportation Research Council/VDOT

Joseph Weber, chief of biodiversity information and conservation tools in Virginia’s Natural Heritage Program at DCR, developed the Wildlife Biodiversity Resilience Corridors dataset. This map is publicly available as part of the online Natural Heritage Data Explorer.

Drawing from data in the Virginia Natural Landscape Assessment and ConserveVirginia, the map represents areas of relatively high biodiversity, low fragmentation relative to surrounding landscapes, and high environmental diversity, providing a variety of refugia and, thus, contributing to biodiversity resilience.

“Wildlife Biodiversity Resilience Corridors include and connect every ecoregion in Virginia — running along coasts, traversing the Piedmont and winding through mountains and valleys,” Weber said. “Through many connections with one another, they span Virginia’s lowest and highest points, from sea level to the summit of Mount Rogers. If conserved, they may provide an undeveloped landscape for populations of species to adapt and move over the long term.”

The plan identified 26 “nexus areas” where the wildlife-vehicle conflict areas intersected with the biodiversity corridors. These areas may be studied further as potential sites for mitigation actions, which could include signage for drivers or fencing to guide wildlife to existing underpasses.

What happens next? The Virginia Department of Transportation has been awarded a Federal Highway Administration grant for more than $600,000. With this funding, through the federal Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, Virginia’s state agencies will identify roads with the highest risk of large mammal collisions.

For more information, visit this Story Map.

Categories

Natural Heritage | Nature