Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Conserve. Protect. Enjoy.

Department of Conservation and Recreation

Department of Conservation and Recreation

By Haley RodgersPosted October 05, 2023

Why apply?

I was drawn to the Virginia Master Naturalist basic training because ultimately, I knew becoming a master naturalist would help me be a better environmental science communicator for DCR. I also wanted an excuse to spend more time in nature, meet fellow nature lovers and learn more about Virginia’s flora and fauna.

The Pocahontas Chapter Virginia Master Naturalist Graduating Class of 2023

Another important reason was to become a more informed community volunteer. This program is designed to get more volunteers into nature throughout Virginia, because our public lands need all the support they can get to care for the natural resources, wildlife and outdoor recreation facilities we are collectively responsible for.

I applied to the Pocahontas Chapter’s basic training in the fall of 2022 and heard back in December that I was accepted. From January to May 2023, I had a new weekly ritual of going to Pocahontas State Park for class on most Tuesday nights and attending field trips on select weekends.

The training course

The 40-hour Virginia Master Naturalist basic training course is offered by 30 chapters across the commonwealth. The course schedule and cost vary by chapter. My experiences reflect taking the course from the Pocahontas Chapter.

Native plant class display

Each class was three hours and is meant to be a crash-course on the week’s topic (all related to natural resources, including plants, animals, insects, fish and more). I thought that a three-hour class would be hard to stay engaged with, but I found myself fascinated with each class. The instructors for each topic taught me so much. Each instructor inspired me in one way or another with their passion for their niche.

The field trips were my favorite element of the program. Hands-on learning and field experience really helped new information stick.

Field trip: Bat monitoring

After a crash-course on bats and why they are an important part of our ecosystem, we had a bat monitoring field trip at Pocahontas. Liz Revette with the Friends of Pocahontas State Park taught us how to set up bat monitoring technology/stand and then the real fun happened at dusk.

Setting up to monitor bats and the bat monitor IDing echolocation frequencies

Once the bats started to fly around, the microphone on the special technology picked up the frequencies of the bat’s echolocation and depicted which bat species was flying above us. We reported our findings as citizen scientists – meaning we reported data that scientists could use to track health and populations of bats.

Field trip: Vernal pools

Salamander eggs and even larvae were seen in this vernal pool in Charles City, Virginia

Until the vernal pools class, I didn’t know what a vernal pool was! For those who aren’t familiar, it’s a temporary body of water that forms in the spring from water runoff and thawing ice, but then dries up come summer. Since it cannot support fish, the lack of predators makes it an ideal breeding grounding for salamanders. The vernal pool we visited was full of salamander eggs, as well as some salamander larvae.

Field trip: Frog watch

Fowler's toad (all toads are frogs, but not all frogs are toads)

One evening at Pocahontas we wandered around quietly, paying attention to the ribbits we heard. Thanks to our lesson from the Department of Wildlife Resources, I was able to identify which kind of frogs were croaking. We reported our findings as citizen scientists for this activity as well, again to give scientists data for tracking the health and populations of frogs.

Field trip: Birding

Between two groups of classmates, accompanied by experienced birders, we identified 53 species in just a couple hours at Pocahontas! We used eBird to report our sightings, again to contribute to citizen science.

Cedar waxwings in a tree

Some of my favorite sightings:

Field trip: Herpetology count

Spotted salamander found under a log

During the herpetology count, I felt like a kid again, roaming through the forest looking under all the logs to see what we could find. It was so exciting to see a spotted salamander for the first time! We reported our findings to the Virginia Herpetological Society, which works to protect reptiles and amphibians.

Field trip: Tree IDing

I have always considered myself a tree-hugger, but I was excited to start becoming a tree ID-er too! We walked around Pocahontas looking at various trees and learning how to distinguish a tree’s species by looking at qualities like leaves or needles, bark, branching, fruit, flowers and buds.

There were more field trips and topics covered than I have featured here, but in sharing some of my favorite experiences, I hope you get a sense of how rewarding this program is.

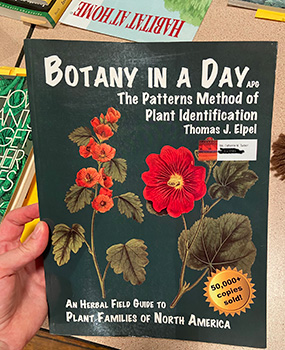

After all classes and field trips are complete, there is an open book final exam

Volunteer hours

It’s expected that everyone who takes the training course will actively volunteer as a Virginia Master Naturalist on approved environmental projects that suit your interest and schedule. To achieve the status of Certified Virginia Master Naturalist requires 40 hours of approved volunteer service.

My first volunteer project was removing invasive plants at the James River Park with a team from DCR (click here to watch a short video on Instagram recapping our work efforts). I live very close to the James River Park system and regularly enjoy their trails, so I was happy to make a difference in a place that gives me so much joy.

DCR employees pulling invasive species at James River Park, March 2023

I also have racked up volunteer hours by volunteering to organize birding outings with a local group of birders who work to be inclusive to anyone interested in learning more about birds and our environment they call home. It has been a joy to introduce birding to fellow nature lovers and see birding become a more popular activity.

Post-graduation

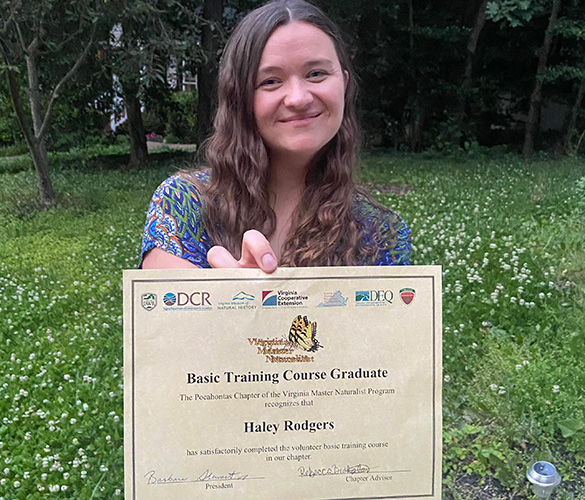

Haley Rodgers proudly holding her basic training certificate

Besides a piece of paper, a T-shirt and a group photo with my classmates, I’ve gotten the following out of the master naturalist program.

Friends: My classmates, who love nature as much (if not more) than I do, became my good friends! During class, we were given a break for dinner (in the form of a potluck) and time to socialize. I appreciated the chance to build connections and even learn new recipes from the potluck contributions. Since graduation, I’ve joined the chapter’s Book Club, met up with classmates to go on plant-ID/birding hikes and stayed connected on our social media group. I am grateful this program introduced me to people from all different walks of life who I may not have met otherwise.

Education and a heightened curiosity: To achieve certification, you must take eight hours of continuing education (CE) courses, in addition to the training. And to stay certified, you must complete eight hours of CE annually. Since the pandemic created a huge increase in free online courses, it was easy for me to complete this requirement and I look forward to learning more. Some of the CE courses I attended:

Confidence: I feel more confident as an environmental science communicator and park volunteer.

A full cup from giving back: I find it rewarding to support my local environment by volunteering with local nature-based organizations and friends groups that support Pocahontas State Park and the James River Park system. To stay certified, I will also be completing 40 hours of volunteer service annually.

Appreciation: An increased appreciation for nature – how resilient, complex and beautiful it is.

I highly recommend anyone else to apply to the Virginia Master Naturalist program! Applications for the next round of trainings in 2024 are now open for many of Virginia’s chapters.

Find your local chapter here. Learn who is accepting applications currently and apply!

DCR is a sponsor of the Virginia Master Naturalist program.

Categories

Conservation | Native Plants | Natural Heritage | Nature

Tags

ecosystem | invasive plants | native plants | state parks